Paul Simon: The Life

BOB ON PAUL SIMON

Read more about Bob's thoughts on and decision to write Paul Simon: The Life and Bob's coverage of Paul's Zimbabwe concert below.

|

When the Library of Congress established the Gershwin Prize in 2007 to salute contemporary songwriters who, in essence, best uphold the grand tradition of the Great American Songbook, its choice for the prize was Paul Simon—an honor whose significance was underscored by the list of subsequent honorees: Stevie Wonder in 2008, Paul McCartney in 2009, the team of Burt Bacharach and Hal David in 2010 and Carole King in 2011.

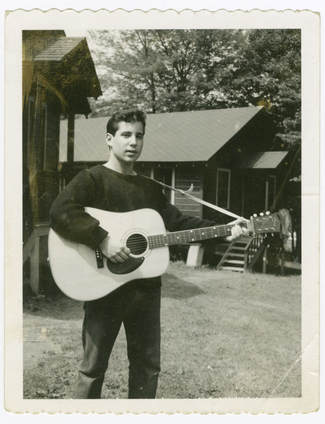

Simon was honored first and he deserved to be. His work, more than that of anyone else of the rock era, demonstrates a gift for beautiful melodies and seductive rhymes that best rivals the songs of such landmark writers as Cole Porter, Johnny Mercer and Harold Arlen. Simon has combined the discipline and craft of that Songbook tradition with the more individualistic sensibility and cultural commentary that is the foundation for the most distinguished music of the second half of the 20th Century. “Still Crazy After All These Years” is classic Songbook. “Homeward Bound” is pure rock. “Mrs. Robinson” blends both traditions. The Gershwin Prize is just one of many accolades for Simon, including an unsurpassed three Grammy Awards for albums of the year as well as nine other Grammys, the Kennedy Center Honors recognition, the Songwriters’ Hall of Fame’s Johnny Mercer Award and the internationally-focused Polar Award. He, too, has been inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Science, and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame twice—first in 1990 as a member of Simon and Garfunkel and in 2001 for his solo work. Yet the most persuasive way to describe Simon’s artistry and cultural reach is simply pointing to the nearly 200 songs he has written since entering the nation’s pop consciousness in early 1966 with a No. 1 single, “The Sound of Silence,” that reflected the restless alienation of young people who saw the nation’s core values tarnished by racial injustice and the escalating conflict in Vietnam: And in the naked light I saw Ten thousand people, maybe more People talking without speaking People hearing without listening People writing songs that voices never share No one dare Disturb the sound of silence. Simon continued in the 1960s to build upon that early promise—moving through such other cultural touchstones as “I Am a Rock,” “The Boxer,” “Mrs. Robinson” and, perhaps the most celebrated ballad of the pop-rock era, “Bridge over Troubled Water.” By 1970, when many of his peers were either losing creative steam or doomed to spend the rest of their careers recycling their early hits, Simon, 28, was just getting started. As he moved into his solo years, he not only expanded his subject matter to include the complexities of adulthood, but he also exhibited more striking melodies and more varied, aggressive musical textures. In “American Tune,” written in the early 1970s amid the disillusionment of Watergate and the continuing war, Simon captured the national mood, but with an underlying compassion that contrasted sharply with Bob Dylan’s early rage: I don’t know a soul who’s not been battered I don’t have a friend who feels at ease I don’t know a dream that’s not been shattered Or driven to its knees. Oh, but it’s all right, it’s all right For we’ve lived so well so long Still, when I think of the road We’re traveling on I wonder what’s gone wrong I can’t help it, I wonder what’s gone wrong. Across the emotional spectrum, he wrote a song, “Something So Right,” that spoke about commitment in relationships with an openness and honesty that rivaled John Lennon’s most vulnerable admissions—but again with a sense of comfort, not confrontation: Some people never say the words “I love you.” It’s not their style To be so bold Some people never say those words, “I love you.” But like a child, they’re longing to be told. Through acclaimed albums, such as “Still Crazy After All These Years,” and great, but neglected ones, notably “Hearts and Bones,” Simon kept searching for new themes to express the nuances of the human condition, as well as new musical seasoning—from the lure of reggae to joyful lift of African rhythm—and it all came together in the wit and warmth and wonder of his “Graceland” album in the summer of 1986. |

While these songs have spoken about our lives and times with such an intimacy and grace that they share an important place in our cultural consciousness, we know little about the composer.

That’s chiefly by Paul Simon’s design. Through four decades of enchanting music and tens of millions of record sales, publishers and music fans have hoped for a quality book by or about Paul Simon, but he has turned down numerous offers to write his autobiography and has refused to grant interviews to those who attempted a biography. He, too, has discouraged people close to him from speaking with writers. This blackout is now over. Simon has given me his blessings for what will be his definitive biography. We have already begun a series of extensive interviews in which he speaks candidly and in depth about Simon the artist and Simon the man. He is so committed to this biography that he is encouraging scores of key people in his life to finally break their silence—all with no strings attached. Simon’s importance rests in his artistry—and that artistry will be the centerpiece of the book, but the songs take on an even more evocative edge once we know the personal journey that produced them. Simon’s music is so eloquent and accessible that it feels effortless, but we will learn of the struggle behind the songs and the stardom. In his music, Simon has shared the darker moments of his journey in several of his songs, never perhaps more nakedly than in “The Boxer,” which came early in his songwriting career as he conveyed the burdens he’d carried and burdens he knew were yet to come: In the clearing stands a boxer And a fighter by his trade And he carries the reminders Of every glove that laid him down Or cut him till he cried out In his anger and his shame, “I am leaving, I am leaving” But the fighter still remains. In the book, we will convey the resilience and resolve of a man who withstood those punches and emerged triumphant, not only with one of the most prized collections of songs in the history of American popular music, but with a personal life that in the long run has brought him the comfort he so sought when writing “Bridge over Troubled Water.” As chief pop music critic for the Los Angeles Times for more than three decades, I have known Paul Simon ever since his early solo days. I’ve interviewed him at various points in his life, even accompanied him to Zimbabwe in 1987 for his celebrated “Graceland” concerts. We have talked during times of great success for him and severe disappointment. Meanwhile, Paul’s journey continues. His latest album, “So Beautiful or So What,” contains some of the loveliest music of his career. It was named one of the five best collections of 2011 by the New York Times’ Jon Pareles. He’s now working on another album and continues to tour. In the end, Simon’s story will be an inspiring and illuminating look at personal struggle and artistry. |

PAUL SIMON ON SOME OF HIS OWN HITS

The Boxer

"Looking back, I don't recall thinking I went through years so struggle. I was never poor and I had a family that loved me. But I have to say singing 'his anger and his shame' still makes me feel uncomfortable, so there must have been some anger and shame."

American Tune

"I always think of that as my Nixon sore-loser song. I was writing about what I felt was the end of the sixties beliefs - the idealism - in the lines, 'I don't know a soul who's not been battered. I don't know a dream that's not been shattered.'"

Graceland

"It seemed to be about finding something you could call a state of grace - the healing of a deep wound. And that's what was going on in South Africa. There was a deep wound and then an attempt the healing process"

Bob on the Radio

|